Center for Philosophy of Science, University of Pittsburgh

40th Anniversary Lecture Series

March 14, 2002

IS PHILOSOPHY OF SCIECE ALIVE IN THE EAST? A Report from Japan

Soshichi Uchii

Kyoto University

Abstract

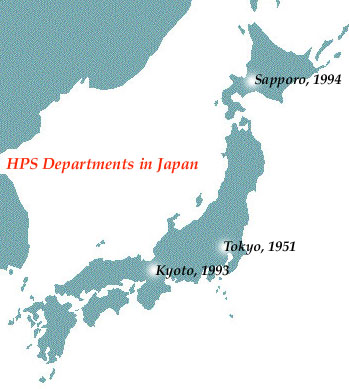

Do you know the Japanese equivalent for "philosophy"? That word, "tetsugaku", was coined after the Meiji Revolution (1868). Do you know when the standard philosophy of science, in the form of the logical empiricism, was introduced into Japan? After the World War II, around 1950. Do you know whether or not the philosophy of science, especially its "hardcore", is studied seriously in Japan? Very few people are studying the philosophy of space and time, the philosophy of quantum mechanics, the philosophy of evolution, the philosophy of probability, or the philosophy of social sciences. Do you know how many HPS departments exist in Japan? Only three, one is founded in 1951 and its graduate program was extended in 1970, and the other two were founded around 1993. Now, with these preparations, you are beginning to understand what I am going to talk about---Is Philosophy of Science alive in Japan? I will briefly outline the history of the philosophy of science in Japan, and discuss some of its peculiarities. And from this discussion, I wish to point out what is needed for the philosophy of science in Japan.

Here is an Outline:

1. Three Basic Facts (1868-2002)

2. Taketani's Doctrine of the Three Stages (1936-1968)

3. Logical Empiricism (1950-1970)

4. Scientists and Philosophers (1950-2002)

5. "New" Philosophy of Science (1970-1995)

6. What is needed for Japanese Philosophy of Science? (1991-????)

Thank you Merrilee, for your moving introduction!

First of all, I wish to thank the Center for Philosophy of Science, and the Director Jim Lennox, for inviting me to this wonderful Celebration of the 40th Anniversary of the Center. I am going to talk about what is going on in the field of philosophy of science in my country, Japan.

Now let me give you an Outline of my talk (as in the Abstract). It is divided into 6 Sections. After reviewing the history and the peculiarities of Japanese philosophy of science, I would like to say my opinion in the final section, as regards what we have to do in order to improve it.

1. Three Basic Facts

I will show you Three Basic Facts about Japanese Philosophy. The peculiarities of the Japanese philosophy of science may be better understood in light of these facts.

(1) Fact One: Japanese Philosophy begins in Meiji Era

The Fact One is that the Japanese equivalent of the word "philosophy"---"tetsugaku"---was coined (1874) in Meiji Era, together with many other words used in philosophy. People in Meiji Era (1868-1912) combined Confucianistic concepts and Buddhistic concepts, and coined new words; then scholars as well as laymen adapted themselves to these new concepts and words. By inventing new words, Japanese people somehow produced new elements in philosophy, as they tried to understand it. Thus, Nishida, Tanabe, and the so-called "Kyoto School of Philosophy" emerged from such efforts of understanding and misunderstanding of this new discipline of philosophy.

(2) Fact Two: Logical Empiricism introduced after the World War II

A similar thing happened again after the World War II. The Logical Empiricism (the standard philosophy of science), together with analytic philosophy, was introduced as a newest brand of western philosophy in Japan. This is the Fact Two. In relation to this, the Department of History and Philosophy of Science was founded in 1951 at the University of Tokyo (at Komaba). The University of Tokyo had the only department of that kind in Japan until 1993; which means that they monopolized the market for philosophers and historians of science in our contry. I should remind you that I visited the Center for Philosophy of Science in the Fall of 1991, and at that time I was a Professor of Ethics at Kyoto. After my return to Kyoto, I got involved in the plan of founding a new chair for history and philosophy of sciece, and needless to say, my experience in Pittsburgh helped a lot, in order to make a persuasive plan.

(3) Fact Three: Marxist Philosophy of Science emerged in the 30s

The Fact Three is that we had a Japanese version of the philosophy of science, before the World War II. It already existed in the late 30s, and its major proponent was Mitsuo Taketani (1911-2000); he published his Doctrine of the Three Stages of Scientific Development in 1936. I will explain its content in a minute, but before that, we have to see its background, since the Fact Three is relatively unknown by the western philosophers.

Taketani and Yukawa

Taketani was a physicist, and he collaborated with Hideki Yukawa, for some period; Yukawa is of course the first Japanese Nobel Laureate (1949, physics), a national hero among the Japanese people. In 1935, Yukawa published a monumental paper, "On the Interaction of Elementary Particles, I", and introduced a new particle called "meson", in order to explain both the strong interaction and the weak interaction between elementary particles. But here, I will illustrate only the strong interaction within the nucleus of an atom.

Yukawa thought that the binding force within nucleus, between proton and neutron, for instance, can be explained only by introducing a new particle, about 200 times heavier than electron.

A number of other papers followed along this line. And Taketani's name appears in two of them. In addition to physics, Taketani was very much interested in the Marxism and social activities, and he came to his own view of the development of scientific knowledge: how the theories of science change and become better and better.

2. Taketani's Doctrine of the Three Stages

With this background, let me explain Taketani's Doctrine, the first instance of Japanese philosophy of science. He applied the Hegelian Dialectic to the scientific development. Hegel's Triad is, Thesis, Antithesis, and Synthesis; there is an opposition between the first two, but it is resolved by the third, unifying the whole. Applying this scheme to the scientific development, Taketani's triad is, Phenomenon, Substance, and Essence. And corresponding to this Triad, we have the three stages of scientific development.

Taketani's Doctrine became popular after the War. After the War he became free to say whatever he wanted, and many scientists were influenced by this doctrine; for one thing, Taketani's activities during the war gave him a strong credit. Taketani's Doctrine flourished in the 50s and the 60s.

Taketani asserts that science may start from descriptions of our experience---this is the Phenomenal Stage---, but it does not end there. Next, science asks what sort of substance may make up the objects of experience, and what sort of structure they may have---this is the Substantial Stage. And this second stage necessarily raises the question of the essence of that substance and the phenomenon---this is the subject for the Essential Stage, a synthesis of the previous two stages. The process does not end here, but continues a similar cycle at a higher level.

We can make this schematic exp]anation more concrete, in terms of the Newtonian Astronomy. Astronomy started from observations of stars. Their movements seen from the earth show some regularities; these phenomena were described, sometimes by means of mathematics. This is the Phenomenal Stage. But people had to introduce various things, such as the constituents of the universe and their real (as opposed to mathematical) structures, and Kepler discovered his three laws of the planetary motion. Taketani says that these laws are Phenomenal laws but the inquiry reached the Substantial Stage which necessitates the consideration of the essence of such regularities and movements. And finally came Newton; he discovered the three laws of motion and the inverse square law which determines the attractive force between any two bodies in the universe. Such forces are the essence of the solar system, and the Newtonian mechanics belongs to the Essential Stage, thus giving a unified view of the world.

In the field of nuclear physics, where Taketani mainly worked, Taketani claims that Yukawa's theory of meson opened the Substantial Stage, by introducing (substantial) entities called "meson".

Ambiguities and Difficulties

Although Taketani's Doctrine attracted a number of scientists, I do not think it can be supported by historical instances. Moreover, there are some ambiguities at the core of this Doctrine, which cause two major difficulties. First, what is the criterion for distinguishing the three stages? Taketani seems to confound many things. Logical distinction, ontological distinction, and epistemological distinction. For instance, if Phenomenon and Substance are ontologically distinct, there is no opposition between the two, unlike Hegel's Thesis and Antithesis.

More serious is the Second difficulty, with respect to his assertion that the three stages are repeated at a higher level. I do not understand his logic for saying that a theory of essence becomes a phenomnon at a higher level, and goes through a new Substantial Stage and reaches a new Essential Stage. This makes sense only as a sloppy metaphor. For instance, the Newtonian theory of gravity was replaced by Einstein's general relativity; but what is the "substance" and the "essence" in this new development? Taketani can give no unique answer. Taketani's assertion of the "spiral structure" of the development seems to be nothing but a loose metaphor, with no definite answer for a specific case.

A Digression: Taketani's Stories

Let's make a digression. There are a number of funny stories about Taketani, and let me tell you some of them. (The source is Taketani 1982, pp.19-41.) Taketani's paper on the Three Stages was published in a Journal published by a group of young intellectuals from various fields, such as aesthetics, French literature, or philosophy. Taketani joined them; they tried, through their defence of culture, to fight against the Japanese imperialism which was preparing the invasion to China, Taketani recalls. But the Special Police (in charge of political and ideological matters) began to arrest members of this group in 1937, the year the Japanese Army began the invasion. Taketani was arrested (first time) in September, 1938, and spent 8 months in jail. He describes this incident as follows:

At last, in April, a procsecutor began my examination. I showed him a number of foreign journal papers in which our work was cited, and appealed what important work we were doing. This had some effect, and several days later, the procsecutor called Mr.Yukawa, and by making him a guarantor, shelved my indictment and freed me.

Yukawa became the professor of mechanics of Kyoto Imperial University the same year, 1939.

Freed from jail, Taketani knew the news of nuclear fission. And a few years later (1942), he began to do research on the possibility of atomic bomb by military mobilization. But he was again arrested in 1944, because a member of Taketani's informal group for discussing the problem of technology was arrested and the police suspected Taketani's view on technology might be dangerous; Taketani was on the police file anyway.

This time, Taketani explained to the police that he was doing research on atomic bomb, and warned that if the United States were to succeed in making the bomb before Japan, just one plane carrying a bomb would suffice for destroying the city of Tokyo in a second! But the police never believed such a tale. Taketani got ill during the summer, and he was permitted to go home for treatment of the illness. He feared that America might have succeeded in making atomic bomb and appealed so to the police and the prosecutor in charge of him. In the meantime, he read Potsdam Declaration in a newspaper in late July and judged that his fear was not premature.

Ten days later, Hiroshima was smashed! He visited the prosecutor, and told him that the bomb which destroyed Hiroshima was nothing but an atomic bomb, and declared that Japan was defeated; astonished prosecutor gathered all colleagues in order to listen to Taketani's lecture!

3. Logical Empiricism in Japan

Logical Empiricism was introduced into Japan after the World War II. But people began to understand it only after two major books were translated into Japanese.

Reichenbach's Rise of the Scientific Philosophy, by Saburo Ichii, 1954, and Ayer's Language, Truth, and Logic, by Natsuhiko Yoshida, 1955.

Personally, I was inspired by Ichii's translation of Reichenbach's book, when I was a student of engineering, and decided to study philosophy; Ichii's translation was crisp and clear, and Reichenbach's ideas and passions were communicated very well. I liked Ichii's plain language, which is quite different from the language of those philosophers of the Kyoto School.

Aside from Ichii, many young philosophers actively introduced logical empiricism into Japan. However, in retrospect, they made too much emphasis on logic and language. They all agreed that logic is an indispensable means for studying logical empiricism; and it is quite understandable that they were very much impressed by the power and the beauty of mathematical logic. They eagerly studied logic, and emphasized the importance of linguistic analysis; but they did not go far enough, as far as the philosophy of science is concerned. They fell somehow short of absorbing the philosophy of space and time, or the philosophy of quantum mechanics, for instance.

This sort of unbalanced digestion of the logical empiricism, I believe, is responsible for producing a widespread misunderstanding of the philosophy of science in Japan: even today, many laymen confound the philosophy of science with the analytic philosophy in general.

Ichii meets Taketani

During the 50s, one of the most active philosophers of science in Japan was

Saburo Ichii (1922-1989). He first studied chemistry, but went to England and studied under Karl Popper in London. He translated various works by Russell, Popper, Reichenbach, and introduced the Oxford ordinary language school to Japanese philosophers. But I wish to mention Ichii's confrontation with Taketani. They collaborated, together with others, for founding a new journal for the general public: its title was "The Science of Thought". However, Ichii, being a disciple of Karl Popper, could not agree with Taketani's Doctrine which heavily depends on Dialectic Logic.

Ichii's criticism was based on his critical examinations of the Hegelian dialectic logic (The source of the following exposition is Ichii 1963). In the Anglo-American world, probably the best known criticism of dialectic is that of Karl Popper (1902-1994) in his paper "What is Dialectic?" (first published in Mind, N.S. 49, 1949, reprinted in Popper 1963). Darwing on Popper's view on Dialectic, presumably, Ichii argues that we can not make a literal sense of Dialectic. Further, he denies the usefulness of Taketani's Doctrine, emphasized by Taketani himself; useful instructions come only from specific analyses of a given problem, not from Taketani's sweeping Doctrine.

But Ichii tries to exploit some common features between Taketani's philosophy and Logical Empiricism. According to Ichii, both despise mere dependence on papers, and try to face the actual science and its concrete history; although Taketani lays emphasis on a global consideration of history, Logical Empiricism gives more weight to logical analysis.

Then Ichii cites Herbert Feigl's view which distinguishes four levels of scientific explanation (Feigl 1949):

(1) the level of descriptions,

(2) the level of empirical laws,

(3) the level of first order theories, and

(4) the level of second order theories.

Ichii interprets that (1) and (2) together roughly correspond to Taketani's Phenomenal Stage. Moreover, Feigl characterizes (3) and (4) as follows: At these levels we wish to give an interpretation regarding the structures of light, matter, electricity, etc. These theoretical levels have constructs about the microscopic structures underlying the macroscopic phenomena which are observed; that is, they contain either various postulates about entities or constructs of abstract and mathematical order. Ichii asserts that "postulates about entities" roughly correspond to Taketani's Substantial Stage, and "constructs of abstract and mathematical order" to the Essential Stage; thus, at least to this extent, the philosophy of logical empiricism and Taketani's Doctrine may approach to each other.

But of course there are differences as well. First of all, according to Taketani's Doctrine, the essence-theory in a certain period may be construed as an element of the new Phenomenal Stage, thus making a spiral development anew; but nothing of this sort in Feigl's theory. Thus Taketani may argue that the empiricist's theory is inadequate in that it can see the development of science as merely a gradual and somehow homegeneous process; it does not do justice to the dynamic nature of science, and it neglects a qualitative difference between any two stages, and hence it cannot give a good guide for scientific inquiries, such as Yukawa's theory of meson.

I don't have to continue their debate any further, since I have already pointed out the basic ambiguities in Taketani's Doctrine. The debate boiled down to the treatment of Dialectic, and neither Taketani nor any other Hegelians succeeded in presenting a persuasive reason for adopting Dialectic logic, distinct from ordinary logic used in mathematics and science; above all, no one succeeded in giving a definite content to "Dialectic".

And, unfortunately, Ichii himself left the "hardcore" part of the logical empiricism and went to the philosophy of history.

4. The Relationship between Philosophers and Scientists in Japan

Next, let us see the relationship between philosophers and scientists in Japan. In the movement of logical empiricism, philosophers learned scinece and scientists learned philosophy. Now, how was the situation in Japan in this respect?

It seems that similar things happened in Japan too. Nobushige Sawada (the former president of Philosophy of Science Society Japan) witnesses that a series of philosophical symposia were held in the 50s, and mathematicians, physicists, and philosophers gathered in order to discuss common themes. However, a famous physicist disliked "old fashioned" philosophers who came from Kyoto and uttered unintelligible words; and this physicist consulted younger philosophers (including Sawada) with better understanding of science, and proposed to make another group for discussion, which lasted, eventually, for well over ten years, until the physicist died (Sawada 1997, 6). Such activities as this prepared the ground for establishing a professional association for philosophy of science in Japan.

Also, we should notice that several young scholars with scientific training turned to philosophy; aside from Saburo Ichii already discussed, Shozo Ohmori (1921-1997) and Hidekichi Nakamura (1922-1986) should be remembered. All of them became a very active advocate of philosophy of science in Japan, at least when they were relatively young. Ohmori was one of the founders of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Tokyo (Komaba), and raised many philosophers. And Nakamura, who was a mathematician and turned to philosophy, was unique in that he tried to unify the Marxist philosophy and the logical empiricism (unsuccessfully, in my opinion).

So far, good. However, here, I have to tell you a strange story. An association for philosophy of science was in fact founded in 1954, and the physicist Hideki Yukawa contributed to this event. However, the title of this association does not have the Japanese word for philosophy; its name sounds something like this: "Association for the Foundational Studies for Science". And to make things worse, the English translation of its name is: "Japan Association for Philosophy of Science (JAPS)"! Why this strange discrepancy between the Japanese title and its English translation? Yukawa is largely responsible for this. Yukawa argued against adopting the word "tetugaku"---Japanese equivalent of "philosophy", you may recall---, and his reason was something like this: "Most scientists do not like that word so that it is disadvantageous for attracting many scientists as members; so we should adopt a more roundabout expression." Here, I am again almost quoting Sawada's witness (Sawada 1997, 6-7). You have to notice that Yukawa was, and still is, a national hero for Japanese people. Besides, Yukawa's view does seem to represent the majority of scientists.

Thus, Japan Association for Philosophy of Science started in 1954; but that was not the end of the matter. Many philosophers were frustrated. There were two groups, one with the name "American Philosophy Group", the other with the name "Logic of Science Group"; and they decided to meet annually with the title "The Meeting for Philosophy of Science", and its first meeting was held in 1957. And these meetings led, eventually, to founding another association, with the literal title of "Philosophy of Science" (in Japanese) in 1967; that is the Philosophy of Science Society Japan (PSSJ). Thus we now have two associations for philosophy of science, which is quite unusual in the world. And this reflects the relationship between philosophers and scientists in Japan.

Maybe I should mention another evidence. We have a bureaucratic organization called "Science Council of Japan", which belongs to the Ministry of public management, home affairs. This has two large divisions, the Division of Hmanities and Social Sciences, and the Division of Natural Sciences. The former consists of 3 subdivisions, and the latter 4 subdivisions. PSSJ belongs to a subdivision in the Humanities, and JAPS belongs to a subdivision in the Natural Sciences. Thus the Japanese philosophers of science are divided into the both sides of a large gulf between Humanities and Natural Sciences! The fact that we have two associations for philosophy of science, somehow reflects the present state of the philosophy of science in Japan. And I think this is quite contrary to the spirit of the Logical Empiricism.

Be that as it may, members of JAPS (and also of the later PSSJ) produced a significant work: Kagaku-jidai-no-Tetugaku (Philosophy in the Age of Science) 3 Vols, edited by Jun'ichi Aomi and others, published by Baifukan, 1964. This work is interdisciplinary and exhibits a glimpse of the spirit of logical empiricism. For instance, one of the editors, Jun'ichi Aomi (1924-) was a professor of jurisprudence at the University of Tokyo; he studied Gustav Radbruch---German philosopoher of law---and many other German authors, but he was also quite sympathetic to the analytic traditions of Anglo-American philosophy, and became one of the leading figures of Russell studies in Japan. This sort of open-mindedness is quite rare in Japan.

Anyway, despite this highlight, the trend of logical empiricism rapidly faded away in Japan, because there arised in America a new trend of philosophy of science around 1960, and younger philosophers in Japan became busy introducing this new trend, instead of digesting the legacy of logical empiricism which was quite tough. A sad pattern repeated again and again since Meiji Era in Japanese academic world, in the field of humanities!

5. Japanese Followers of the "New" Philosophy of Science

I do not have to explain, to the American audience, what the "New" philosophy of science is. As you well know, the epoch-making book in this trend was Kuhn's Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962, 2nd ed., 1970). He was primarily a histrorian of science, but in this book, he propounded a new way to look at science. Instead of interpreting scientific activities in terms of logic and facts, you should see the social aspects of science, the way scientists solve problems, the way they change the norm and standard of their activities. He introduced the distinction between Normal Science and Scientific Revolutions. Japanese followers of this "new philosophy of science" quickly introduced the new trend, without paying due regards to the legacy of the logical empiricism.

Murakami came to the foreground

The first department of history and philosophy of science in Japan was founded in the University of Tokyo at Komaba in 1951; and its graduate program began in 1970. And this department has produced many able philosophers and historians of science; but by far the most famous among them is Yoichiro Murakami (1936-). Murakami is one of many disciples of Shozo Ohmori. Ohmori was one of the founders of philosophy of science in Japan, but he gradually left this subject and formed his own philosophy of more esoteric kind. Instead, Murakami came to the foreground, as far as philosophy of science is concerned.

Murakami, together with his students, produced a tremendous amount of Japanese translations of many authors, most of whom belong to the new generation after the logical empiricism; to mention a few, Norwood Russell Hanson, Paul Feyerabend, and Imre Lakatos (one of Popper's disciples). These translations appeared in the 70s and the 80s; and although other translations, those of Popper, Carnap, and Hempel, for instance, were also going on, Murakami and his collaborators overwhelmed others.

Prof. Murakami has retired from the University of Tokyo, and he is now teaching at International Christian University. He has wide interests, writes well, and each of many of his books clears a certain standard which may be hard to clear for mediocre scholars.

It must be said that Murakami and his collaborators attracted a wider audience, and contributed to drawing people's attention to the philosophy of science. However, he has never touched on such tough subjects as the philosophy of space and time, of quantum mechanics, or of probability. Thus, although he raised many students as his collaborators, these fields are almost as poor in Japan as when we began to import logical empiricism after the World War II. Thus the unbalanced state of the philosophy of science was enhanced by Murakami and his collaborators.

My point may become clearer if we make some comparison. Take Russell Hanson, for instance. He was one of the sources of the "new philosophy of science" by emphasizing the theory-ladenness of observations on the one hand. But he was also involved in the philosophy of quantum mechanics, on the other hand. Philosophy of space and time, and philosophy of quantum mechanics owe a lot to Reichenbach, and in the U.S., these became a major field of philosophy of science attracting many brilliant scholars; thus although Russell Hanson criticized the "standard view", he retained important legacy of logical empiricism. This attitude is not adopted, generally speaking, in Japan; and Murakami is no exception.

Murakami pursued up-to-date topics in the philosophy of science, and more generally, in the recent science studies; thus in recent years he seems to have left the philosphy of science in the narrow sense, and transformed himself to a proponent of STS and other newer branches of science studies. He is now eager to discuss the ethical issues for the scientist and the technologist. As long as you see the activities of these eminent "philosophers of science" in Japan, you may suspect that the philosophy of science (without quotes) is almost dead in Japan, and you may feel gloomy. But this may be a bit premature. From now on, I will tell you my own personal view.

6. What is needed for the Philosophy of Science in Japan?

Not all disciples of Ohmori are like Murakami. Prof. Ishigaki, one of the founders of HPS at Hokkaido University (in Sapporo) comes from philosophy but became an expert of the philosophy of quantum mechanics. He is now raising young students in this field. Prof. Tanji of Tokyo Metropolitan University, who was a visiting fellow here, also works on the philosophy of quantum mechanics, as well as on other topics.

And here, I may talk about my own work. Being a graduate of Kyoto University, I have nothing to do with Ohmori. I am pround of being one of Arthur Burks's students. I told you that I was inspired by Reichenbach's book. When I was working on my Ph. D. thesis on causality and induction with Prof. Burks, I had also interest in the philosophy of space and time; but I had no time to spare for this subject.

After getting back to Kyoto, I was occupied by many other things, including job-hunting. I had several technical papers published in English, but most Japanese philosophers could not understand them. So I had to write more "soft-core" papers in Japanese, in order to get a better job.

Fortunately, after several years of my struggle, I was employed by Osaka City University in 1979, but the job was for teaching ethics. However, I managed to teach logic and some piece of philosophy of science, in addition to ethics. After all, the Japanese word for logic is only slightly different from the word for logic !

While in Osaka City University, I began to work on the philosophy of evolution. Also, I found a physicist there interested in the philosophy of science, and together with a few colleagues, we had a small discussion group, and we taught the physicist logic and philosophy, and he in return taught us analytic mechanics and quantum mechanics.

In addition, I made some historical research on the roots of the probabilistic inductive logic; as a byproduct of this research, I wrote a popular book on Sherlock Holmes (1988), which gave me some reputation among people.

I also published a book on ethics (1988), treating both the contractarian trandition and the utilitarian tradition; and I believe, mainly because of this, I was nominated to the chair of ethics at Kyoto University in 1990. But I came far away from the spacetime philosophy, and I almost gave up to work on this topic; I was already 47 years old.

It was around this time that an invitation came from Jerry Massey, the former Director of the Center. He was looking for an Asian scholar, as a visiting fellow of the Center, and luckily, one of my former students were staying in Pittsburgh as a visiting scholar. I had some personal troubles, but eventually I could visit Pittsburgh in 1991. And although my stay was short, this experience revived my interest in the philosophy of physics, and of space and time in particular, for the reasons you may well know. I should point out that even in the 90s, there were no Japanese philosophers working on this subject, space and time.

However, while I was in Pittsburgh, I was working on Maxwell and Boltzmann, the history of statistical mechanics, and on the theory of natural selction by Darwin and Wallace. I had to complete these works in order to begin anew my effort to examine relativity theories and the philosophy of space and time.

Thus, around 1995, I started what I should have started 25 years ago. I began to examine Reichenbach's books, Gruenbaum's opus magnum, Sklar's books, Friedman's renowned book, Earman's crisp and condensed books, and more recent works by a number of historians and philosophers. As a result, I have posted about 100 files, mostly in English, on the problems of space and time on the web, as course materials in these three years. Here are some sample pictures used in my course materials.

Young Einstein with a positive and a negative curvature

Old-aged, flat Einstein

All I can do may be merely to catch up with these scholars in this field; but I think this is quite important for the future philosophy of science in Japan. Unless some philosophers do this belated work, a crucial part of the philosophy of science would be missing forever in Japan.

Blank Hole or Black Hole?

That would be a "blank hole" in the Japanese philosophy of science. Instead, we need to study a "black hole", which is quite instructive as John Wheeler says; we can gain, by such a study, many useful insights into the nature of space and time, as well as insights into the relationship between physics and philosophy. Fortunately, there are a few young students interested in this field in our department. By raising them properly, I think I can contribute to transplanting the spirit of the founder of the Center for Philosophy of Science, to Kyoto and Japan.

Pitt Magazine, March 2002, photo by S. Uchii

I hope the next generation of Japanese philosophers of science can make a better contribution in this field. And, finally, I wish to say "thank you" from Kyoto.

References

Ichii, Saburo (1963) Philosophical Analysis, Iwanami.

Feigl, H. (1949) "Some Remarks on the Meaning of Scientific Explanation", in Readings in Philosophical Analysis, ed. by H. Feigl and W. Sellars, Appeleton-Century-Crofts.

Popper, Karl (1963) Conjectures and Refutations, Routledge and Kegan Paul.

PSSJ (1997) Thirty Years of Philosophy of Science Society Japan, Philosophy of Science Society Japan.

Sawada, Nobushige (1997) "The History of the Philosophy of Science in Japan", Kagaku Tetsugaku (Philosophy of Science) 30.

Taketani, Mitsuo (1968) The Problems of Dialectic, Keiso-shobo.

Taketani, Mitsuo (1972) The Quantum Mechanics, its formation and its logic, 3 vols., Keiso-shobo.

Taketani, Mitsuo (1982) The Social Responsibility of the Scientist, Keiso-shobo.

Yukawa, Hideki (1935) "On the Interaction of Elementary Particles, I", Proceedings of Physico-Mathematical Society of Japan. Reprinted in Collected Papers of Hideki Yukawa, vol. 10 (ed. by Y. Tanikawa and R. Kawabe), Iwanami, 1990, pp. 75-84.

March 25, 2002. (c) Soshichi Uchii

suchii@bun.kyoto-u.ac.jp